The two rival factions of the Katipunan, started out as mere sangguniang balangay (councils). Andres Bonifacio presided over the founding of both. The Magdiwang was formed in Noveleta, Cavite on April 2, 1896; the Magdalo, in Kawit, Cavite, on April 3, 1896. Due to their rapid growth in membership, the two branches were elevated by the Kataastaasang Sanggunian (Katipunan Supreme Council) to the status of sangguniang bayan (provincial councils), after which the two groups were authorized to form balangays under them and to expand their influence. The rift between the two groups grew when Spanish forces assailed Cavite in the latter part of 1896; the rift grew further after the liberation of Cavite.[1] The two factions began their own regional government with separate leaderships, military units, and “mutually agreed territories.” The rivalry was limited to the province of Cavite and some parts of Batangas because these areas were already liberated and thus revolutionists could freely move and convene. The rift never culminated into violence. At times, the two groups were cordial and fought side by side against their common foe, the Spaniards.[2]

On March 22, 1897, two rival factions of the Katipunan, the Magdiwang and the Magdalo, met at the administration building of the friar estate in Tejeros, San Francisco de Malabon in Cavite.[3] The meeting on March 22 had clear objectives, according to the memoirists Artemio Ricarte and Santiago Alvarez: the planned defense of the liberated territory of Cavite against the Spanish, and the election of a revolutionary government. The meeting was first presided over by Jacinto Lumbreras, a member of the Magdiwang faction, who would later yield the chair to Bonifacio when it came time to address the reorganization of the revolutionary government. The Katipunan was a well-organized revolutionary movement with its own structure and officers. It had an established system that included provincial units. But during the Imus assembly of December 31, 1896, proposals to either transform and revise the organization of the Katipunan or replace it with a revolutionary government organization fomented.

Only three months since the Imus assembly had convened, Bonifacio once again took his place as presiding officer for the same purpose of assessing the kind of governing structure the Katipunan needed in order to best fulfill its goals. In Imus, no resolution was made despite an attempt to determine what the revolutionary government would be. The convention in Tejeros, on the other hand, successfully organized an assembly of predominantly Magdiwang members to elect leaders for the revolutionary government. While no one knows the total number of delegates present in the historic event, 26 names were recorded, 17 of whom were from Magdiwang (according to Santiago Alvarez),[4] and 9 from Magdalo (according to Emilio Aguinaldo and Carlos Ronquillo).[5] Ronquillo also noted that many unnamed participants were in the upstairs area of the estate house “filled to capacity.” Some of the present were also from parts of Batangas and some provinces to the north. Hence it is difficult to determine the exact number of voters present then.

According to historian Jim Richardson, a substantial number of delegates present, though affiliated with Magdiwang, could be more accurately be tagged as “independents” who did not necessarily support Bonifacio.[6] This brings in new factors to the election that took place. Records only mention those who won, but not the number of votes.

The election results were as follows:

| Position | Winner | Affiliation | Other Contenders |

| President | Emilio Aguinaldo | Magdalo |

Mariano Trias (independent) Andres Bonifacio (Magdiwang ally) |

| Vice President | Mariano Trias | Independent |

Andres Bonifacio (Magdiwang ally) Severino de las Alas (independent) Mariano Alvarez (Magdiwang) |

| Captain General | Artemio Ricarte | Independent | Santiago Alvarez (Magdiwang) |

| Director of War | Emiliano Riego de Dios | Independent |

Ariston Villanueva (Magdiwang) Daniel Tirona (Magdalo) Santiago Alvarez (Magdiwang) |

| Director of Interior | Andres Bonifacio | Magdiwang ally |

Mariano Alvarez (Magdiwang) Pascual Alvarez (independent) |

Here is the list of the members of the Kataastaasang Sanggunian or Supreme Council in the Katipunan prior to the election at Tejeros. The Council was composed of the four most important positions into the Katipunan office—the pangulo, the kalihim, the tagausig, and the tagaingat-yaman:[7]

| Name | Position | Term[8] |

| Andres Bonifacio | President (Pangulo) | 1895-1896 |

| Emilio Jacinto | Fiscal (Tagausig), Secretary (Kataastaasang Kalihim) | 1894-1895 |

| Pio Valenzuela | Fiscal (Tagausig) | 1895 |

| Vicente Molina | Treasurer (Tagaingat-yaman) | 1893-1896 |

Mariano Alvarez, in a letter to his uncle-in-law, noted that fraudulence marred the voting process in Tejeros:

[…] Before the election began, I discovered the underhand work of some of the Imus crowd who had quietly spread the statement that it was not advisable that they be governed by men from other pueblos, and that they should for this reason strive to elect Captain Emilio as President.

These events were greatly upstaged, in memory at least, by the ensuing tiff that occurred between Andres Bonifacio and Daniel Tirona.

The latter raised provocations when he insinuated that Bonifacio was unfit to take on his position owing to a lack of credentials. Tirona loudly called for the election of one Jose del Rosario, a lawyer. The proverbial salt had been rubbed against the wound—what vexed Bonifacio most was not so much the attack on his credentials but rather the lack of due process. He had, after all, reminded the assembly gathered at Tejeros that the will of the majority—however divergent from each individual’s, must be respected at all costs.

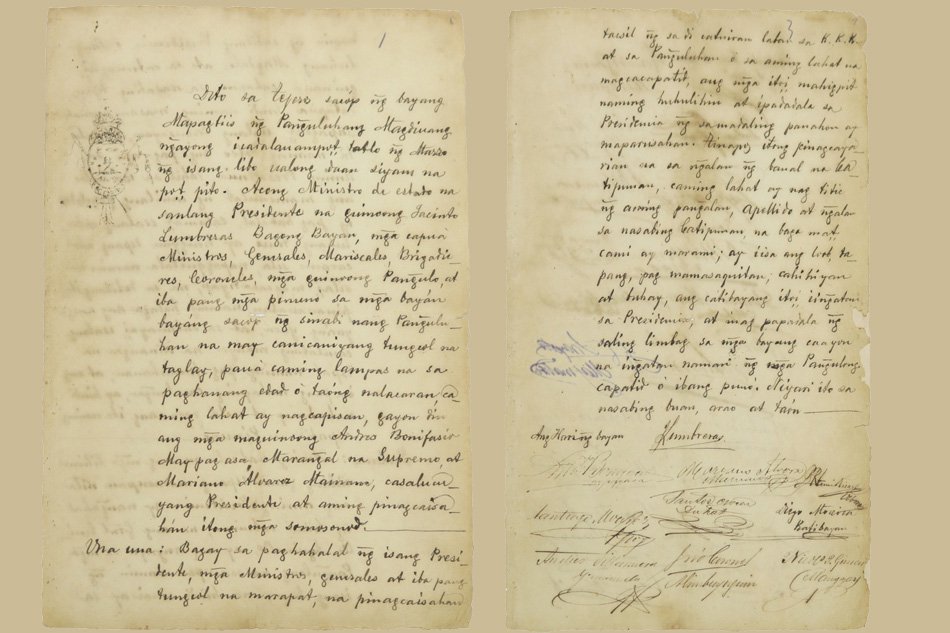

Bonifacio’s resolve would, a day later, become manifested in a document called the Acta de Tejeros, which proclaimed the events at the assembly to be disorderly and tarnished by chicanery. Signatories to this petition rejected the republic instituted at Tejeros and affirmed their steadfast devotion to the Katipunan’s ideals. This declaration and the intention of starting a government anew would later cost Bonifacio his life. He would be tried for treason by a kangaroo court and sentenced to death at Maragondon, Cavite on May 10, 1897.

Contentious as the events surrounding Tejeros are, both in intention and outcome, it was undoubtedly a pivotal moment in Philippine revolutionary history. A school of thought argues that the assembly at Tejeros exposed how the Caviteño elite had besieged the revolt of the masses. Another perspective offers the shift from a revolution of mystical and masonically organized aims to one adhering to 18th and 19th century rationalist and deist lines, imbued with the characteristics of principalia used to command.

Contentious as the events surrounding Tejeros are, both in intention and outcome, it was undoubtedly a pivotal moment in Philippine revolutionary history. The first school of thought argues that apart from organizational structure and personality politics, Tejeros would betray the realignment in the leadership and goals of the revolution. The assembly at Tejeros exposed how the Caviteño elite had besieged the revolt of the masses. Another perspective offers the shift from a revolution of mystical and masonically-organized aims to one adhering to 18th and 19th century rationalist and deist lines, imbued with the characteristics of principalia used to command.

The Phases of the Philippine Revolution

The Philippine Revolution against Spain occurred in the years of 1896 to 1898. In the spirit of providing context for historical events, the PCDSPO, together with military historian Jose Antonio Custodio, jointly produced the following maps that illustrate in detail the various offensives and counter offensives launched by both Filipino and Spanish forces during the revolution.

ENDNOTES

[1] Jim Richardson, Light of Liberty: Documents and Studies on the Katipunan, 1892-1897 (Manila: Ateneo de Manila, 2013), 321.

[2] Ibid., 322.

[3] Ibid., 323.

[4] Ibid., 325.

[5] Ibid., 326.

[6] Ibid., 329.

[7] Ibid., 44-45.

[8] Ibid., 416-422.

FURTHER READING:

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A., History of the Filipino People. Quezon City: Garotech Publishing, 1990.

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. The Revolt of the Masses: The Story of Bonifacio and the Katipunan. Quezon City: University of the Philippines, 1956.

- Kalaw, Teodoro M. The Philippine Revolution. Rizal: Jorge B. Vargas Filipiniana Foundation, 1969.

- Ricarte, Artemio. Memoirs of General Artemio Ricarte. Manila: National Heroes Commission, 1963.

http://malacanang.gov.ph/tejeros-convention/